Zero Tolerance = Mission Impossible? Rethinking AB/C strategies in high risk economies

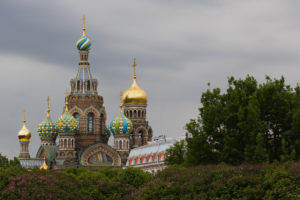

Photo Credit: Wikimedia

A recent Foreign Affairs article by Chris Miller highlighted how “the three-pronged strategy of Putinomics” has worked to keep the current resident of the Kremlin in power:

“First, it focused on macroeconomic stability—keeping debt levels and inflation low—above all else. Second, it prevented popular discontent by guaranteeing low unemployment and steady pensions, even at the expense of higher wages or economic growth. Third, it let the private sector improve efficiency, but only where it did not conflict with political goals.”

Those in the field of anti-corruption should pay close attention to this playbook, especially the third-prong, and consider how it could be used by other autocratic states to appease the population while resisting efforts to hold the corrupt accountable.

This disturbing trend of repressive statecraft should give pause to groups working to make their governments more transparent and accountable, particularly here in Asia, where governments are more and more leaning towards “guardianship” states or worse mimicking the heavy handed styles of Russia and China. A serious re-evaluation of current anti-bribery and corruption (AB/C) strategies is needed if we are to effectively confront this problem.

While it may be unreasonable to expect a tidy three-pronged approach to the problem, there are interesting insights coming out of the Philippines. The Ramon V. del Rosario Center for Corporate Responsibility of the Asian Institute of Management promotes AB/C preventative measures and has gained significant headway in raising awareness of global best practices in AB/C controls in Philippine companies. This is an important first step as these companies face many challenges implementing compliance in harsh, very high risk environments where “corruption and cronyism are pervasive.”

At the same time, is it really possible for companies to adopt a zero-tolerance stance in highly corrupt ecosystems? Should we rethink how we use collective action in addressing systemic corruption?

A current study on Tri-Sectoral Collaboration at the Singapore Management University suggests we should look at partnerships not really as different parties sharing mutual goals but rather as the integration of divergent interests. This kind of mindset is important especially for those who would like to engage a wide range of sectors in the fight against corruption. Too often it is assumed “that people who resent corruption will more or less inevitably become active supporters. Overlooked, as a result, are many low-level networks and social processes that…still help build trust, organizational skills, and local leadership”

Lastly, it is important to think of new ways to effectively address systemic causes of corruption, not just the symptoms. As the recent Panama and Paradise papers reveal ever more disturbing incidences of global corruption, each country, including in the Philippines must look at “how other countries made corruption low reward and high risk.”

Jose Solomon B. Cortez is a Project Consultant for the Ramon V. del Rosario Center for Corporate Responsibility of the Asian Institute of Management