Your Supply Chain Is As Strong As the Weakest Link – Part II

Photo Credit: ITprogBlog

This article originally appeared in the TFM Magazine, Volume 2 Number 13, 2018, p. 32 – 35.

Read Part I here

Empowering through knowledge

One of the most identified risk areas for organisations regarding corruption is third-parties acting on behalf of their organisation. In many cases, a third-party is an SME supplier either working independently on behalf of the larger, more established, organisation or as part of a joint venture agreement.

It is imperative that due diligence is done on all third-party representatives as the UK Anti-Bribery Act extends to organisations that do not have the necessary processes in place to prevent corruption.

Therefore, for a larger, more established, organisation to protect itself, third-party representatives must be educated on the expectations the larger organisation has, with clear guidelines on how business should be conducted. For example, a joint venture agreement must be a legally binding contract with expectations and areas of accountability clearly stated.

Upon misconduct being identified, the first course of action is reporting it to the police, who are mandated with investigating the allegations, evaluating the findings and putting the evidence forward to prosecutors. However, misconduct and corruption are not always as cut and dry. An example of this is below:

ABC Traders is an organisation that is three years old; it has two shareholders. The organisation has done relatively well since its establishment and has secured solid long-term service agreement contracts. However, the shareholders have a massive disagreement and decide to part ways.

Shareholder one opts to continue to run ABC Traders independently and has negotiated an exit payout for shareholder two. Shareholder two accepts the exit payment then immediately establishes another organisation named ABC Holdings. Shareholder two subsequently approaches all the customers of ABC Traders and advises them that the banking details of ABC Traders have changed and provides the banking details of ABC Holdings for all future payments to be paid into the new account.

Within a couple of weeks, shareholder one realises what shareholder two has done. In the mind of shareholder two, no crime was committed; he/she was merely doing business as usual. Upon this case being reported to authorities, the activities of shareholder two were shrugged off and put down to “Business is business, this is not a crime.”

So what is the impact of this on the larger, more established organisation who paid ABC Holdings instead of ABC Traders, taking into account that the signatory to the service level agreement is actually ABC Traders? Importantly, they have no service level agreement with ABC Holdings, therefore, have no guarantees in terms of downstream suppliers being paid. Furthermore, there would be no guarantee that work commissioned would meet any safety or quality assurance standards or that taxes or VAT would be paid over to SARS.

This example highlights that the actions of a corrupt supplier, whether done consciously or sub-consciously, does have an impact on the larger, more established, organisation. This is especially so if the larger, more established, organisation falls under the jurisdiction of international regulators.

It is essential that organisations recognize the risks of corrupt behaviour through their supply chains and ensure that SME’s like Jeremy, ABC Traders and ABC Holdings are aware of the ripple effect impact that their actions have on the organisations they service.

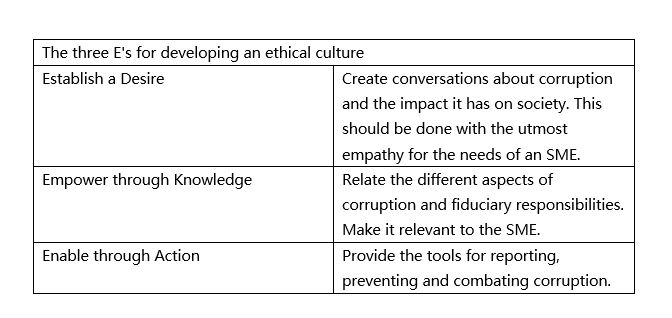

Encourage Clean Business

Once larger, more established, organisations approve a supplier in their supply chain, they need to take the necessary steps to educate them on the benefits and necessities of conducting clean and ethical business practices. Essentially, they have to remove the WIIFM (What’s in it for me?) mentality.

In order to change this WIIIFM mentality, communication must be ongoing and there have to be trusted reporting mechanisms firmly in place.

Many organisations approach anti-competitive risk management through a tick box exercise in which they require their suppliers to attend an induction course, then take a test and sign an acknowledgement letter. Although this method may be enough to comply with the law, it makes no guarantees to influence an ethical culture of an SME.

In many cases, SMEs view this tick box exercise as a means to move forward with a contract. More than any other effective change management process, moving a corrupt business into clean business is an ongoing process incorporating checks and balances that reinforce “Clean Business is Good Business”.

Wybrand Ganzevoort is the Managing Director of Collective Value Creation, which specialises in the development and implementation of Enterprise and Supplier Development (ESD) strategies, with a specific focus on Lean ESD.

Yolelwa Sikunyana is the Founder and Director of Sikunyana Incorporated. She is an attorney with more 14 years in-the-field experience. She has worked with the private and public sectors, specialises in anti-corruption compliance, contractual law and funding agreements.