Politicizing Anti-Corruption Campaigns

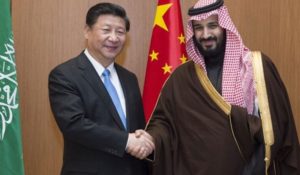

Photo Credit: FARS News Agency

Across the globe, countries have taken varying approaches to combat the problem of corruption. In South Africa, the Parliament finally took steps to hold President Jacob Zuma accountable for his unethical dealings, resulting in his resignation in February 2018. While in Bangladesh, the head of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party Khaleda Zia was recently sentenced to five years in prison for corruption and embezzlement, thus eliminating her from running for Prime Minister.

In recent years, Thailand’s private sector has united to tackle their corruption issue through collective action, while in Brazil open data platforms are becoming a popular tool for reducing misconduct in the country in recent years. While it is clear that fighting corruption should be a main priority for every country, not every anti-corruption campaign is what it appears to be on the surface. At times, these initiatives are executed in a manner that does more harm than good. Two such countries come to mind: The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the People’s Republic of China.

Since being appointed Crown Prince in June 2017, Mohammed bin Salman has been on an aggressive drive to “open up” Saudi Arabia’s traditionally conservative society, both socially and economically. From removing the ban on female drivers to diversifying the Kingdom’s economy away from its overreliance on oil, the young Crown Prince is quickly making waves within his country and beyond. Perhaps no initiative has garnered more attention than the quest to rid the Kingdom of systemic corruption. Launched on November 4, 2017, Saudi Arabia’s anti-corruption campaign aims to eradicate corruption at all levels of government – apparently netting over $100 billion in assets already.

Early returns seem to suggest that the campaign is achieving what it set out to do, however under the mandate of a newly established anti-corruption committee, dozens of previously “untouchable” royals, businessmen and senior government officials have been arrested, without due process. While many of these people are indeed guilty of engaging in illicit behavior, the Saudi system is set up to financially to favor the royals and their allies, therefore anyone targeted under this campaign was likely favored by the royal family at some point in the past.

Similarly, Chinese General Secretary Xi Jinping has embarked on a far-reaching campaign to rid the Chinese Communist Party of corruption. Ever since economic reforms began in 1978, political corruption in the form of bribery, graft, and kickbacks have become the norm across the state. This increase in corruption led Xi to vow to crackdown on “tigers” (powerful leaders) and “flies” (lowly bureaucrats) in a full-scale effort to reform the Communist Party and its image among the population.

Like the Saudi campaign, on the surface it looks like Xi’s campaign marks a positive step towards combatting corruption. However, corruption allegations can also be used as cover for Xi and his allies to limit dissent and keep people in line. The recently established anti-corruption agency (National Supervisory Commission) has expanded powers to detain people for months at secret locations without access to lawyers.

What makes China and Saudi Arabia’s corruption crackdowns dubious in the eyes of many is that the governments have long had power over the public, private, and state-owned sectors – any recent investigations into corruption begs the question of why that individual or firm, versus another? When the answer is often it is politically expedient, it is difficult to imagine the results of these campaigns will provide meaningful change for citizens or the business community.

Amol Nadkarni is a Program Assistant for Global programs at the Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE)