Corruption in Trade: It’s the system, stupid

“If the soul is left in darkness, sins will be committed. The guilty one is not he who commits the sin, but he who causes the darkness.”

Victor Hugo

Run a simple Google search with the keywords “customs” and “corruption,” and you will get approximately 34 million results. There is a good reason for that. Corruption and customs administrations go hand in hand, and have since the beginning of trade.

It is no wonder that every once in a while the general public receives a startling glimpse into the disastrous impacts of corruption in trade such as with the Lebanon explosion last year, or the similarly deadly Tianjin explosion in China. There are also many other less known corruption scandals, including the multimillion dollar La Linea scheme in Guatemala that destroyed former President Pérez Molina. Even Russian President Vladimir Putin is said to have made a fortune granting export licenses in exchange for commissions while he was deputy mayor of St. Petersburg and head of the Committee for Foreign Economic Relations in the early 1990s.

But corruption in trade goes beyond high profile disasters and scandals. When government agencies charged with managing imports and exports are poorly managed or actively abused, they cause largely unnoticed but devastating losses in revenue, market distortions, and health and security risks. These costs are akin to a hidden tariff that benefits the few at the expense of the many.

Two Major Types of Corruption

Two forms of corruption are common in international trade.

The first occurs when a trader is bringing in or exporting goods legally, but a government official demands or expects a bribe (although they typically consider it a tip) to accelerate the process. This type of corruption thrives in environments characterized by a tremendous amount of bureaucracy and is understood as purposely creating complexity to sell simplicity.

The second type of customs corruption is more dangerous. A trader is importing/exporting something illegal, or wants to avoid paying duties, and so bribes and colludes with government officials. In this situation, both parties are intentionally working together to break the law and reap the benefits. This is the most visible and prominent type of corruption.

Both types of corruption thrive in environments characterized by the following factors

- Complicated procedures and arbitrary decision making. Where procedures are simple and processes quick, there are few incentives to pay under the table to make them so.

- Paper-based, in-person processes. The more in-person interactions, signatures, and approvals needed from government officials and gatekeepers, the more opportunities for bribes to be paid.

- High tax and tariff rates. The higher the tax, the greater the incentive to break the law. It is not uncommon to see the cost of certain goods double or triple after taxes, duties, and other fees are added in.

- Outdated regulatory frameworks that make it extremely difficult to prosecute, or even fire, corrupt customs officials and traders.

- Arbitrary hiring practices based on personal connections or affiliations instead of qualifications and competence. This issue is often overlooked in the anti-corruption literature and has pervasive effects on the overall system.

- Absence of transparency, including limited use of post-audit reviews and checks and balances.

- Poor compensation and working conditions. Not only low pay but factors such as access to decent housing, health care, and schools are contributor to corruption by officials working at the border.

Moreover, the conditions mentioned above are precisely the ones that make trade more difficult, which is why trade facilitation and anti-corruption initiatives are so closely correlated.

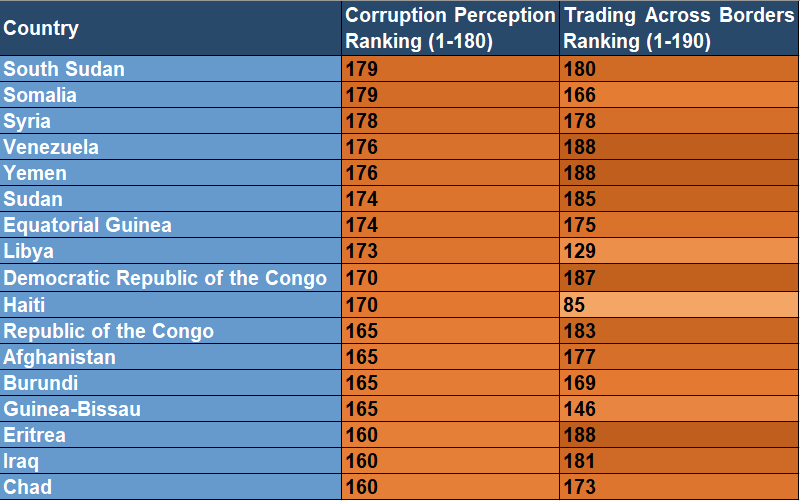

As a matter of fact, a quick look at the Trading Across Borders ranking of the World Bank and the Corruption Index of Transparency International reveals strong parallels between the most corrupt countries and those where international trade is most costly and time consuming.

Unfortunately, current anti-corruption practices in customs and border trade put inordinate emphasis on punishing individuals instead of fixing the system that enables and facilitates corruption. At the end of the day, we are all creatures of our environment and as economists remind us over and over again, we all respond to incentives. In other words, it’s not a case of good apples and bad apples, but rather a case of regular apples in a toxic basket.

A Better Way

The good news is that systems are created by humans and as such we can change them provided that we first acknowledge the role that the environment plays in shaping human behavior. Therefore, governments should treat trade corruption as the systematic and contextual problem that it is, and start making the comprehensive long-term reforms that will eliminate it.

It is no easy undertaking to change an entire system and powerful forces will fight to maintain the status quo. It requires a strong will and a multidimensional and long-term structural approach touching a wide variety of issues far beyond processes and regulations.

At CIPE we have a group of dedicated professionals who are committed to fighting corruption and modernizing trade institutions with a holistic approach that delivers solutions to public and private sector stakeholders alike. If you are interested to know more, please check out our anti-corruption and trade practices.

Aurelio Garcia is Head of Programs, CIPE Trade Department and has over 17 years of experience working in international trade.

Header Image: Creative Commons, Kyle Ryan