COVID-19 is Straining Azerbaijan’s Oil-Dependent Economy

Political scientist Farid Guliyev offers an analysis from Azerbaijan on the economic impacts and corruption risks during the coronavirus pandemic. This blog is the latest in a series taking a look at corruption and COVID-19.

While the global impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has left no economy unaffected, the twin shock of COVID-19 and the oil price collapse has been especially devastating to energy producers like Azerbaijan. As an old but comparably small producer of oil and gas, Azerbaijan tops a list of the world’s most heavily dependent on fossil fuels export earnings. Rock-bottom oil prices and falling global output and demand have had direct and substantially negative effects on the country’s economy.

There are two key things to know about Azerbaijan’s economy which amplify the adverse effects of the pandemic: 1) its persistent oil-dependence, 2) its state capitalist model with state capture.

Oil dependence

Oil accounts for more than 90 percent of Azerbaijan’s exports, and the country does not produce or export any manufactured goods. This fact is well documented. Despite huge potential, agriculture is under-developed and dependent on state subsidies. When the price of oil fell in 2014, the ramifications were so severe that the government had to implement two rounds of national currency devaluations to compensate for the loss in oil revenue. In 2020, the pandemic has dramatically lowered energy demand, driving oil prices down and reducing the amount of oil revenue for the government.

In its May economic update, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) predicted that, while Azerbaijan can tap into its $43.3 billion state oil fund (SOFAZ) in the short run, it will be difficult to maintain macroeconomic stability if oil prices do not bounce back to above $50 levels. Currently, Azerbaijan’s fiscal breakeven price of oil is projected at $78.5 per barrel.

From a global perspective, long-term global renewable energy transition threatens to make the rentier state model of oil-dependent countries obsolete. All states are paralyzed by economic disruption, but Azerbaijan’s economy is one of the hardest hit. Several banks filed for government bailouts and the government is struggling to prevent another devaluation. The central bank is burning through its reserves to keep the currency stable and avoid a socially-disruptive devaluation. The administration of President Ilham Aliyev has responded to the COVID-19 crisis by providing $1.2 billion in fiscal stimulus targeting private firms and individual entrepreneurs. It remains to be seen whether government support will be enough for the revival of small- and medium-sized businesses. However, a bigger challenge is the overall weakness of Azerbaijan’s private sector due to strong state control. Despite a limited liberalization in the 1990s, major businesses are still either owned, controlled or protected by wealthy oligarchs who made their fortunes thanks to close ties with state officials.

State capitalism with cronyism

Azerbaijan’s economy is not a free-market economy, strictly speaking, but is better described as state capitalist with strong crony capitalism features. State and quasi state enterprises dominate the economy and often enjoy monopoly privileges. While small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) were privatized during the post-independence liberalization, large ones still remain under state control. The private sector is small, fragile, and dependent on state funds, subsidies and loans. The share of the total value added generated by SMEs in Azerbaijan equals 6.4% compared to 59% in Georgia and 60% in OECD countries. The fact is that, unlike Eastern European and Baltic countries, Azerbaijan did not accomplish a complete cycle of full-scale privatization and liberalization of markets retaining many characteristics of Soviet-style command economy in management style and organizational structure. Added to this are wide-spread practices of non-meritocratic recruitment, clientelism, and corruption.

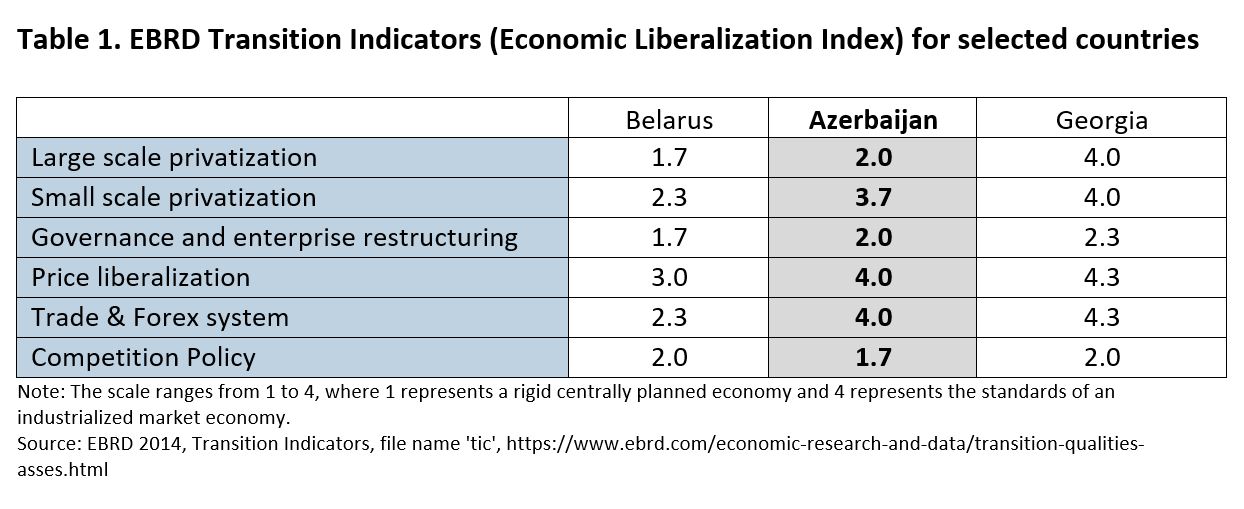

Azerbaijan’s scores on the liberalization index (last measured in 2014) is “limited reform” (see EBRD Transition indicators 2014). While it has advanced in small scale privatization and market-based price mechanisms, so far there is slow or little progress in the privatization of large firms and deficiencies remain in competition policy (see Table 1). Small firms are in private hands, but large companies – such as the national oil company, SOCAR – are state controlled and perform poorly when judged by economic efficiency criteria. The preponderance of the state-owned oil sector not only fuels rent-seeking behavior but also provides weak linkages to the rest of the economy. State dominance is a key impediment to the development of a well-functioning private sector. In neighboring Georgia, where market reform is more fully implemented (it got the maximum score of four in Table 1), SMEs are better prepared to deal with the challenges of post-pandemic recovery.

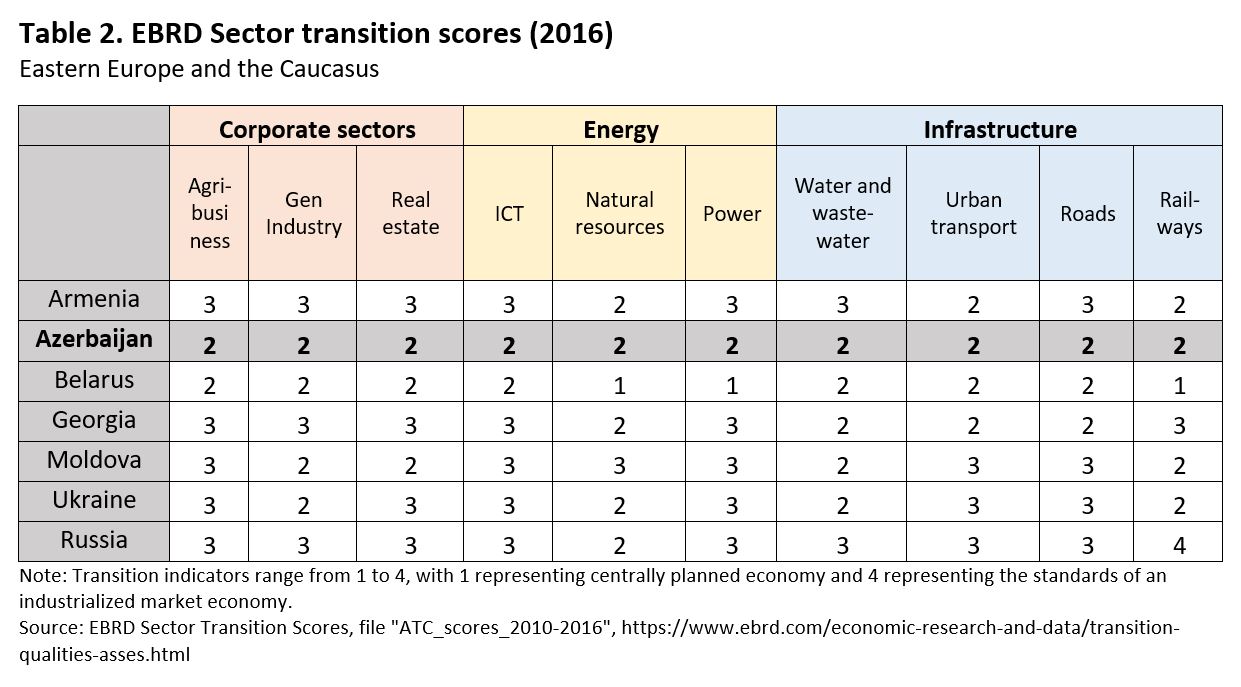

On EBRD Sector transition scores (see Table 2), last recorded in 2016, Azerbaijan performs poorly again, and its scores approximate those of Belarus, a country which is considered to have accomplished few reforms since the collapse of the Soviet Union and which has the region’s highest number of state-owned enterprises. The state exercises direct control over largest companies, especially in the natural resources sectors.

This is likely the result of crony capitalism — an economic structure in which private businesses collude with government officials in some sort of predatory behavior aimed at getting access to, and taking advantage of, public/state resources. Not unlike in many other MENA and post-Soviet countries, Azerbaijan has a crony capitalist economy which benefits state elites in the vicious circle of petro-dollar recycling both within and outside the national economy.

Looking Forward

State intervention during the COVID-19 pandemic is increasing the role of the state in Azerbaijan even more and threatens to undermine the nascent, struggling private sector. Some firms will probably not make it through the crisis. Others that survive will have to adapt to the new reality of a swelled state with increased government powers to regulate economic activities. Government intervention in settings plagued by poor accountability raises the risks of corruption as various state agencies are tasked to manage and allocate large sums to prop up well-connected firms.

A huge informal sector exacerbates Azerbaijan’s pathway out of its resource predicament. The shadow economy accounts for 58% of GDP (Schneider 2010). Altogether, there is no easy escape from this vicious cycle of rentier politics without genuine reform. The government has reiterated its intention to implement reforms through a series of policy packages since 2015, including the appointment of presumably more ‘technocratic’ cadres. Political leaders raised hopes for a moment earlier this year after promising increased transparency in February’s snap elections. However, the elections turned out to be a farce with blatant electoral fraud and the reappointment of many politicians from the previous parliament. In the months since, powerful vested interests (i.e. regime cronies) have used the pandemic to push back against change, delaying once again Azerbaijan’s much-needed reforms.

Image: Wikimedia Commons